A publication of

A publication of

Winter issue 2016 sponsored by

CRE Finance World Winter 2016

7

The Case Against a Commercial Real Estate Bubble

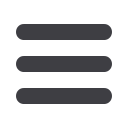

Exhibit 2

Cap Rate Differences

These strikingly similar cap rates are why many in the market today

believe that another CRE bubble has formed. Only by analyzing the

forces behind these cap rates can we make the determination that

we are not in a bubble. In order to do this it is important to analyze

the differences between the constituent components of a cap rate,

the risk-free rate of return and the risk premium, from before the

recession versus the last few years.

The Risk-Free Rate of Return

As a general rule, the higher the risk-free rate of return, the higher

the cap rate should be, ceteris paribus. This is because any

investment needs to compensate the investor for the risk they are

taking (the risk premium) plus the risk-free rate of return that they

would otherwise receive from investing in a riskless asset. Due

to the relatively long-term holding periods for CRE, the ten-year

Treasury rate is often used as the risk-free rate of return. Once again,

it is instructive to look at differences, in this case the ten-year

Treasury rate from the years before the Great Recession versus

the last three calendar years. As you can see in Exhibit 3, there are

some significant differences between rates during these periods.

These equate to about 2% for each of the first two calendar-year

comparisons and not quite 1% for the last comparison. However,

this last difference is a bit misleading. The ten-year Treasury rate

fell dramatically during the flight to quality after the implosion of

Lehman Brothers. Prior to that, the difference was closer to the

2% that we see for the other years.

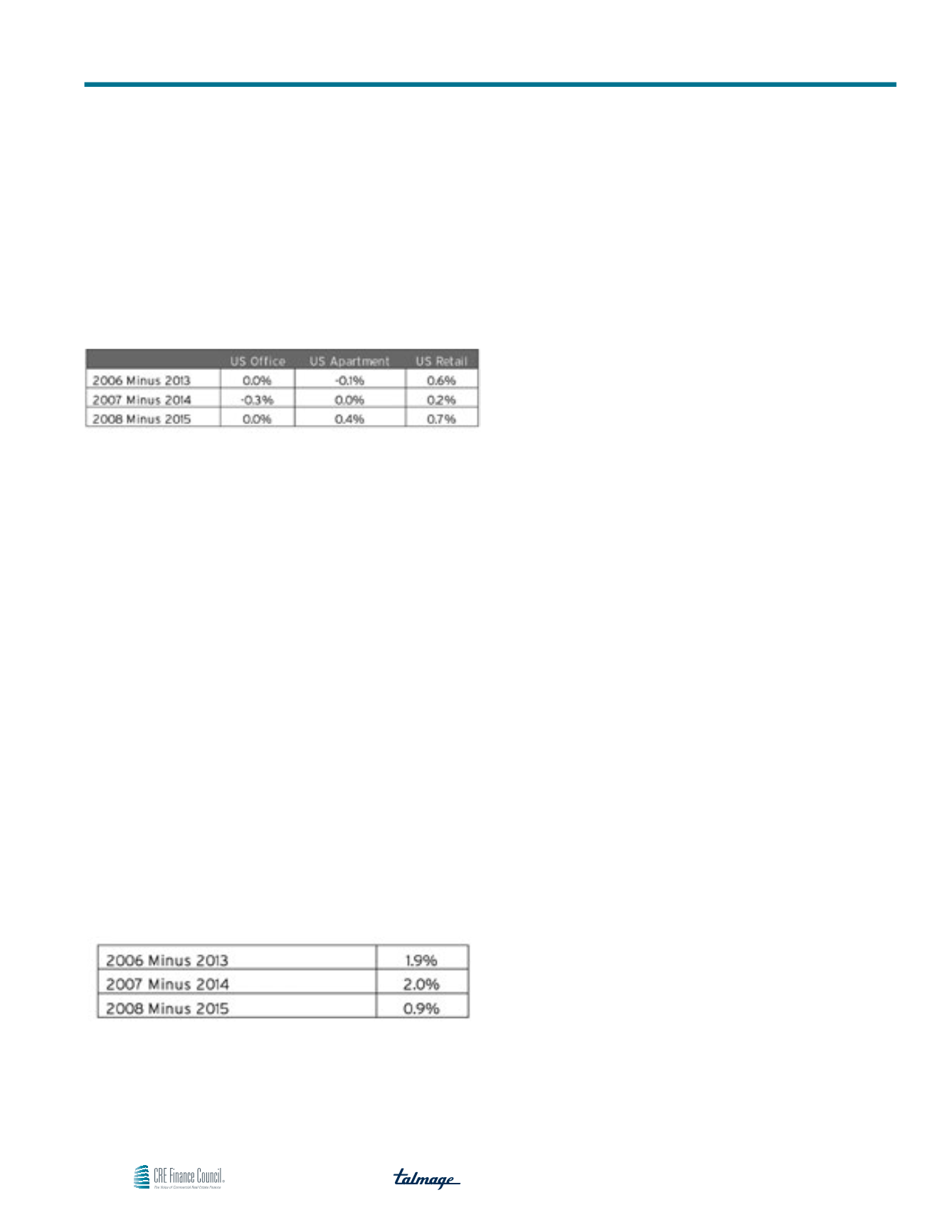

Exhibit 3

Ten-Year Treasury Differences

Ceteris paribus, the data demonstrates that based on the interest

rate difference, cap rates over the last few years should be lower

than cap rates from the years leading up the bubble bursting by

roughly 200 basis points. This therefore makes the environment

from before the Great Recession look like a bubble — cap rates were

too low relative to interest rates. However, in today’s environment,

cap rates are as low as they were before the recession, but that

seems appropriate in the context of ten-year Treasury rates being

roughly 200 basis points lower today than they were during the

bubble period. The instinct here is to conclude that a bubble also

exists today because the Fed is keeping nominal interest rates

artificially low, depressing cap rates, increasing market values

relative to intrinsic values, and creating a bubble.

However, the Fed can only affect interest rates in a limited way and

on a short-term basis. Of course the Fed sets the target Fed Funds

rate, which can be viewed as the benchmark for all other interest

rates. And the Fed’s policies influence (though do not explicitly

control) the rate of inflation, which partially determines nominal

interest rates. But the more critical component is real interest

rates, and the ability of the Fed to influence real interest rates,

especially over the long term, is limited because real interest rates

are primarily determined by the real growth rate of the economy.

Taken together, these two factors perfectly explain the low interest

rate environment of today. Inflation has been declining for a number

of decades as part of a longer-term structural change. However,

since the end of the recession it has been struggling to even reach

the Fed’s 2% target rate. Meanwhile, the real annual growth of the

economy since it began to recover in mid-2009 has been around

2%, below the economy’s long-run average and below the growth

rates achieved last decade before the bubble burst. Therefore, low

interest rates are not due to aggressive monetary policy, but are a

product of today’s slow-growth, low-inflation environment.

The Risk Premium

The risk premium is the other determinant of cap rates. The risk

premium generally derives from two sources — the fundamental

space market and the capital market. The key factor for space

market fundamentals is growth expectations. They are an important

determinant of cap rates because, ceteris paribus, investors generally

pay more for a property with rising cash flows than for one with a

flat or declining cash flows. Therefore, the greater the expectation

of cash flow growth, the greater the downward pressure on cap

rates. By looking at the trends in cash flow growth over time

between the two comparison periods (2006-2009 vs. 2013-2015),