CRE Finance World Winter 2016

8

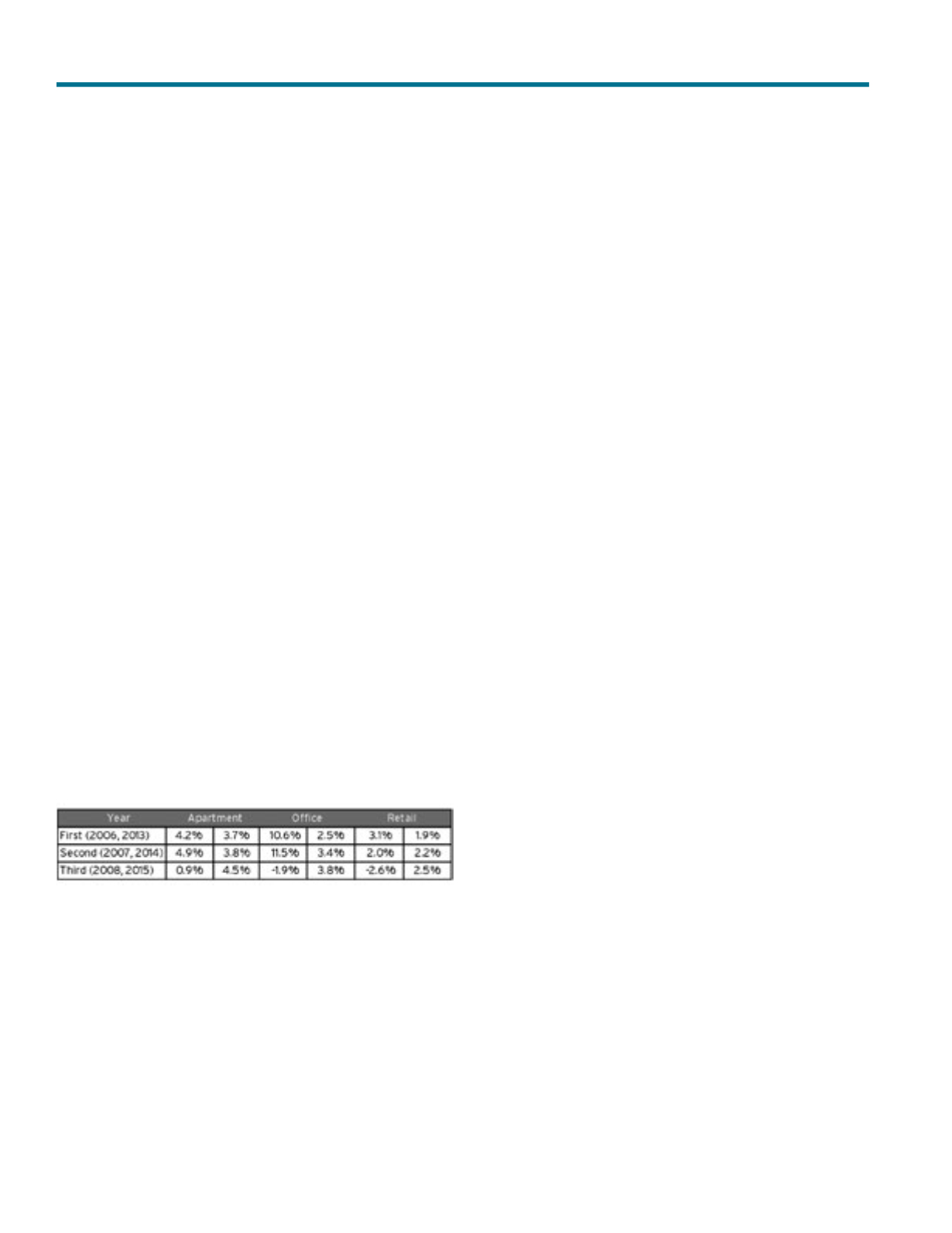

it is obvious that the current environment differs greatly from the

pre-recession environment for each of the three major property

types. The annual cash flow growth rates by property type for the

aforementioned periods are shown in Exhibit 4. Note for 2015,

because the year has not ended, the current forecasted cash flow

growth rates are utilized. However, with three quarters of the year

already completed, the actual growth rates for 2015 are unlikely to

deviate significantly from the forecasted figures.

For the period 2006-2008, growth rates had been accelerating

over time and reached robust levels by 2006 and 2007. The one

possible exception is with retail where massive overbuilding limited

cash flow growth. Problems with valuations arose in early 2008

when the cash flow growth rates began to slow, even before the

CRE bubble burst. Nonetheless, investors continued using highly

improbable forecasted growth rates (anchoring their expectations

to recent positive experience in 2006 and 2007) that were not

going to be ultimately realized. By the end of 2008, the actual growth

rates for office and retail were negative while that of apartment

was slightly positive. All of these growth rates came in well below

expected growth rates that were being used in valuations at the

time. These overly optimistic assumptions about future cash flow

growth caused a compression in the risk premium as investors

believed the strength in the market would continue, just as the

market was about to implode. Consequently, this helped push cap

rates to levels that were too low — market values spiked and deviated

significantly from intrinsic values.

Exhibit 4

Cash Flow Growth Rates by Period

However, for the 2013-2015 period, cash flow growth continues to

accelerate, has not yet peaked, and remains far below the growth

rates from the 2006-2007 period. Moreover, even if the forecasted

cash flow growth rates for 2016 and beyond increase, it is highly

unlikely that they will reach the growth rates from the 2006-2007

period. Although the current positive trends in cash flow growth

and current cash flow forecasts are putting upward pressure on

valuations and downward pressure on cap rates, they are not doing

so to the same extent as before the recession. Essentially, this

is the inverse of what was observed with interest rates. During

2006-2008, interest rates were generally high which put upward

pressure on cap rates. However, the overly optimistic assumptions

about cash flow growth during that period lowered the risk premium

and put downward pressure on cap rates. During the current

period, relatively low interest rates are putting downward pressure

on cap rates. However, because cash flow growth is not nearly

as strong now as it was before the recession, investors are using

more modest (or at least less aggressive) assumptions about

forecasted cash flow growth and consequently the risk premium.

Therefore, downward pressure on cap rates from projected cash

flows exists, but not nearly as much as it did before the recession.

This is causing market values today to be far closer to intrinsic

values than they were around the time the bubble burst.

Capital markets also have a profound impact on the risk premium,

but directly measuring this impact can be a challenge. For example,

the interest rate on commercial mortgage debt can be a poor

indicator because of the risk-free rate component — commercial

mortgage rates could be low simply because Treasury rates are

low, not because the risk premium is low. However, these impacts

can be measured indirectly by the level of CRE debt outstanding —

the more investors are willing to use debt, it intimates that they

prefer taking on risk and/or they perceive risk as being low. This

process results in a compression of the risk premium and consequently

cap rates. Because debt is stated in nominal terms, the absolute

level of outstanding debt is misleading because it will rise over time

as values rise. Moreover, using loan-to-value ratios can also be

misleading because inflated property values can mask excessive

risk taking because the denominator of the loan-to-value ratio

rises along with the numerator and can artificially underestimate

the level of debt and risk.

Therefore, we need to measure the level of debt relative to an

independent factor, like gross domestic product (GDP). Although

property values tend to be positively correlated with the overall

The Case Against a Commercial Real Estate Bubble