A publication of

A publication of

Winter issue 2016 sponsored by

CRE Finance World Winter 2016

9

economy, gross domestic product is a flow metric, not a valuation

metric, and because it encompasses the entire economy it is much

harder to manipulate or artificially inflate. Because debt outstanding

is stated in nominal terms, the nominal GDP must be utilized. In

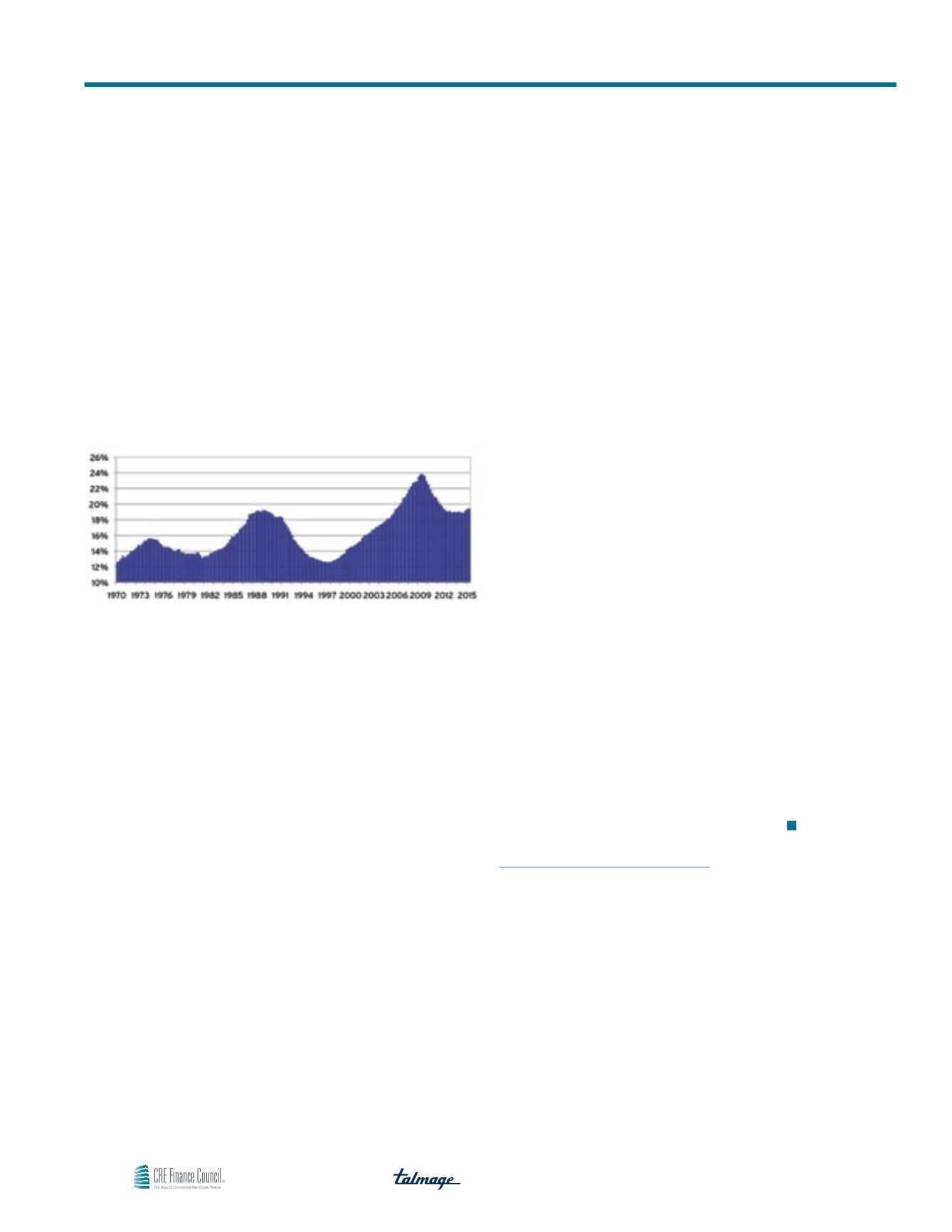

Exhibit 5, the ratio of total CRE debt to nominal GDP is calculated

over time.

Exhibit 5

At the height of the bubble in 2008, when the perception of risk

and the risk premium were excessively low, the ratio of total CRE

debt outstanding to nominal GDP was roughly 24%. This was the

historical peak of this ratio and was reflective of an environment

where the incorrect perceptions of risk pushed valuations up and

the risk premium down. However, as of the most recent quarter of

available data, this ratio has not even surpassed 20%. Therefore,

risk perceptions and the risk premium remain at relatively safe

levels. The 4% or so difference between the current and peak

ratios translates into roughly $720 billion of net new loan issuance,

based on the current nominal GDP. At a rate of $120 billion of net

new CRE debt per year, it would take six years to reach that 24%

level again, assuming no nominal GDP growth. If the economy

continues to grow as most expect, the ratio might only drift marginally

higher, much as it has over the last few years. Therefore, the current

ratio, which is roughly equivalent to the level from 2003 before

the bubble truly began to inflate, does not indicate excessive risk

taking, a mistakenly low perception of risk, or too low of a risk

premium. If anything, it reinforces the notion that the risk premium

prior to the downturn was far too low. Using the current market as

a guide, the risk premium from before the recession was probably

roughly 200 basis points below where it should have been. In this

context, today’s cap rates seem more or less appropriate while

those from before the downturn seem far too low, even though cap

rates from those two periods are incredibly similar.

Conclusion

There is ample evidence to indicate that the current market is not

a bubble. The ten-year Treasury rate, though low, is appropriate

as a function of the current economic environment, not monetary

policy. Cash flow growth, though positive, is low relative to the

period leading up to the recession and is not resulting in underwriting

that is incongruent with probable cash flow growth rates. Lastly,

debt is not being over-utilized as was the case during the pre-

recession period. Investors are generally far more realistic and

restrained during this phase of the cycle using a more appropriate

risk premium.

However, this does not eliminate the possibility that another bubble

could form in the future. As interest rates rise with the continuing

recovery in the economy, the risk premium should decline, keeping

cap rates in a relatively narrow range. However, if discipline begins

to erode and the risk premium compresses too much, it is not

too difficult to envision another environment where cap rates fall

further than they should and market values exceed intrinsic values.

We are not ruling out the distinct possibility of a severe shock

prompting an economic downturn, which might then lead to CRE

fundamentals deteriorating. However, even if such a scenario takes

place, careful analysis will need to be performed before ex post

blanket statements like “Oh, there must have been a CRE bubble”

are issued. Accepting the “bubble” explanation after a downturn

occurs without nuanced thought is sloppy logic.

The Case Against a Commercial Real Estate Bubble

Click Here to Share Comments on this Article