CRE Finance World Summer 2015

32

uring the crisis, the regulators aimed for model accuracy

as their guideline toward normalization of the marketplace.

To jump start the process, regulators applied stress tests

to aid in price discovery and to rebuild capital. They also

set about developing Basel III to permanently close off

regulatory capital arbitrage loopholes identified in the crisis.

Their thesis was that first, if everyone could agree on the fundamental

value of an asset then, where necessary, troubled assets could

be cleared through the system. Secondly, if more sensible capital

charges could be assessed, then the public’s confidence could be

restored in critical financial institutions.

While not the source of contagion in this latest cycle, commercial

real estate (CRE) assets were treated with especial vigor. The

stress tests forced relatively aggressive revaluations of legacy CRE

assets, and risk-based capital reforms are encouraging capital

levels permanently higher along a number of dimensions.

And yet, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) and the

Office of Financial Research (OFR) have never outed CRE as a

source of systemic risk. Each of these bodies publishes an annual

report, which is really more of a review of accomplishments during

the year combined with a risk assessment of the global markets.

None of these reports, at least not as of their most recent, the

OFR’s December 2014 annual, suggests that the CRE sector

poses a threat to financial stability.

Considering that our European counterparts take a very dim view

of CRE, it is interesting to note that for the U.S. regulators, one

of CRE’s minuses may be protecting it from a systemic risk label.

Unlike other traded credit classes, CRE products resist product

standardization, and therefore are limited in the degree to which

they can be integrated into faster-paced trading strategies.

Other product sets that are more actively traded have attracted

a considerable amount of attention from the regulators.

From a systemic risk perspective, CRE debt’s idiosyncratic nature

can be viewed as a strength. If all of our financial products were

standardized enough to be actively bought and sold, then the

system as a whole would be relatively more exposed to herding

behavior. By this measure, CRE represents a stabilizing influence,

because our investors can be counted upon to be somewhat less

reactive in bad times.

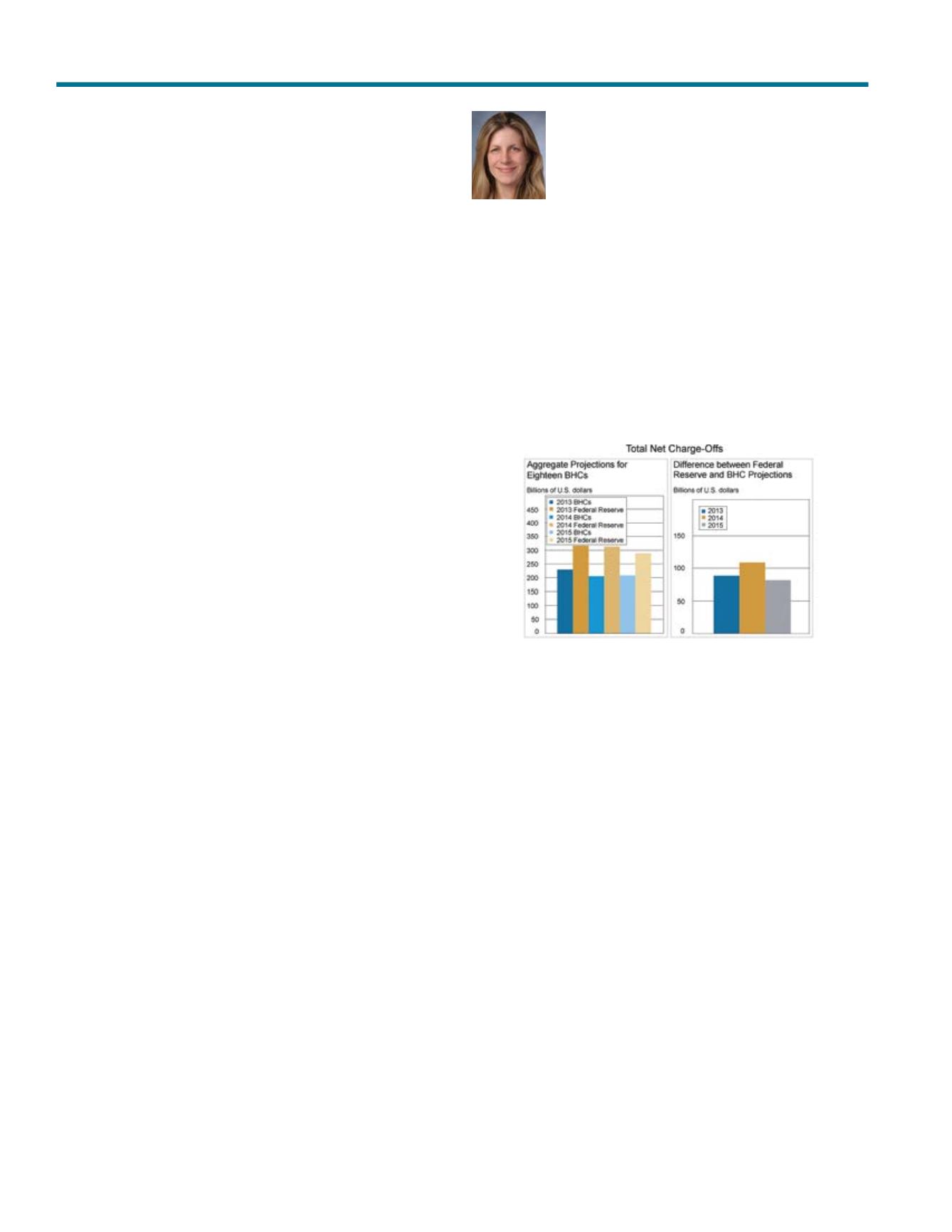

But, enough is often not enough. In their April 6, 2015 Liberty

Street Blog post, members of the New York Fed’s Research and

Statistics Group made the case that over time, the stress tests are

yielding some convergence between regulatory and bank models.

This would be expected, as banks would naturally try to anticipate

their supervisors’ requirements in order to pass the tests. However,

according to this recent analysis, the two sides remain farther apart

still on net charge-off estimates, and especially those related to CRE

loans. That’s not good news for commercial real estate lending.

Chart 1

Breakdown in Differences in Net Charge-Off Projections

Source: Authors’ calculations

On the surface of things, variance between the regulatory and the

industry models can suggest poorly quantified risk-taking on the

part of the banks. Potential model inaccuracies gained attention

well before this spring with earlier analyses by the Basel Committee

on Banking Supervision (BCBS). As part of their efforts to further

refine Basel III, the BCBS has run a series of analyses of bank

capital estimations over time to learn more about bank practices.

At least on the surface, the BCBS has found that despite the

rollout of Basel III, many jurisdictions continue to view capital

requirements differently. Looking below the surface, however,

these differences do not necessarily mean anything other than

the portfolios in question might not be as similar as we think.

To determine whether model variances are a sign of accuracy or

of aggressive risk-taking, further work needs to be done. A model

used to estimate capital requirements for a CMBS portfolio in

the U.S. may act differently than a model used to estimate capital

for CMBS in Italy. Both models could be equally robust, yet the

underlying risks are very different, which could explain even large

variances in capital requirements.

Nuances in product type, market functioning, legal system, and

other factors could easily account for differentials in model output

across banks and especially across jurisdictions. Concluding

that these variances are a sign of problems with the models may

be ignoring valid differences in portfolio fundamentals, and the

regulators may be promoting conservatism over accuracy. Yet, the

D

CRE as a Source of Systemic Risk: How Normative Should the New Regulatory Norms Be?Christina Zausner

Vice President, Industry

and Policy Analysis

CRE Finance Council